Rua Des. Ermelino Leão, 1987

Rua André de Barros, 2010

Rua Cruz Machado, 1987

Rua André de Barros, 2010

Praça Dezenove de Dezembro, 1987

Rua Visconde de Nacar, 2010

Al. Dr. Muricy, 1986

Rua XV de Novembro, 1983

Av. Luiz Xavier, 1983

Praça Dezenove de Dezembro, 2010

Rua XV de Novembro, Teatro Guaíra, 2013 . 0,80 x 2,40m

Rua XV de Novembro, Universidade Federal do Paraná, 2013 . 0,80 x 2,40m

Praça Tiradentes, Catedral Basílica Menor de Nossa Senhora da Luz, 2012 . 0,80 x 2,40m

14 Largo da Ordem, 2012 . 0,80 x 2,40m

Rua João Negrão, Ponte Preta, 2013 . 0,80 x 2,40m

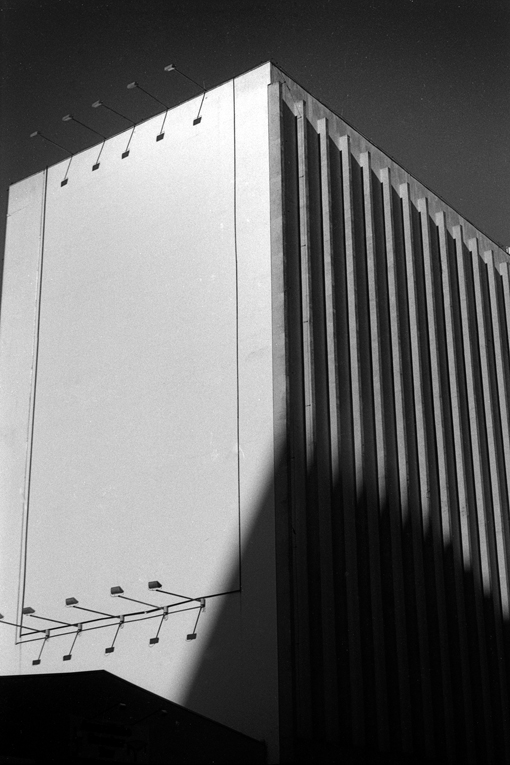

Museu Oscar Niemeyer, 2013

Museu Oscar Niemeyer, 2013

Museu Oscar Niemeyer, 2013

Museu Oscar Niemeyer, 2013

<

>

Curitiba Central

Photographing the central area of her hometown since the late 70's until 2013 when she started an exhibition at the Oscar Niemeyer Museum in Curitiba and released the book with 246 photographs.

critical text

A kaleidoscopic look at Central Curitiba - Rubens Fernandes Junior/ 2013

“In every neighbourhood, there is a madman and everyone knows who this is.”

Paulo Leminski

We know that the photographic technique was born under the domain of reality, which made it legitimate as a way of expression but, at the same time, made it a hostage of the system. It took decades for it to become stigma-free. This stigma is constantly revisited by conservatives since the times of Baudelaire[1], who showed his prejudice and disinterest the same way he prophetically affirmed that photography could corrupt art. This is precisely what happened as photography started imposing itself as a way of expression, information and communication.

Innovative and persuasive, the photographic image became a language that fulfilled the wishes of a new world and irrefutably exerted fascination on the public. Portraits and landscapes were the first genres to be noticed in the photographic processing and, undoubtedly, astounded observers. However, what seemed to be more disturbing for artists and for the art produced in the 19th century was not so much the imitation aspect of photography, which was typical of paintings, but its mechanical and immediate nature.

As Décio Pignatari claims, “the transition from historic to cultural time is the transition from technology to wisdom”[2], which means a lapse of time is necessary to allow learning and mastering new techniques and its proceedings to provoke the emergence of language, the future articulator of the new visual syntax. Photography created a differentiated visual code and constituted, as Susan Sontag remarks, a “grammar” that emerged as free manifestation, detached from any conceptual, moral or ethical ties.

A doubt still haunts me. Why do photographers insist on documenting cities? What is it that makes the artist portray the urban space in different times? Memories, reminiscences, tributes? Or is it just the need to reinforce that photography enables catching a glimpse of non-existent realities? This is the challenge the photographer Vilma Slomp has faced in the last 33 years, which is the creation of a photographic document that transits on a razor edge and on its permanent contradictory condition between reality and fiction, truthfulness and manipulation, space construction and unstable times. The aim is always to surprise the beholder through a wider and more flexible reflection on representation.

The Essay

After looking carefully at Vilma Slomp’s photographs of Central Curitiba, which have been produced since 1979, I observed that she searched for a poetic path to highlight her kaleidoscopic look of the urban space where she lives and transits on a daily basis. She sees the city as a logic drawing, emphasizing fragments, details, traits of its mayors, springs and fountains, the buildings representing the citizen’s cultural identity. As a conclusion, her photography is this kind of logical drawing created on the inaccuracy of her random walks around the city. Through her photos, the city can be understood as a parchment, in other words, layers of memory and times which stir distinct feelings. It seems as if we could see many cities in one, the wooden architecture from the beginning of last century, which refers back to European settlers, eclectic brick projects based on neoclassicism, modern architecture of reinforced concrete. After all, a city like any other in Brazil, where rich urban heritage representing various periods of national culture have been understated and lost the battle to real estate speculation.

Vilma Slomp’s knowledge of the urban space and her interpretation build up a personal and exclusive experience. She manages to make images touch and interlace. This photographic documentation, which, in a way, distances itself from her previous work when it comes to proceedings, shows traces of an essay that sometimes highlights the investigation of lights invading the urban space and therefore creating shapes that insinuate before our eyes, and sometimes prioritises the direct record of a visible world creating categorical representations. All this experimentation confirms her versatile and authentic creative intervention.

The essence of the records concentrates on the expanded central area, stage of the biggest urban transformations, with its streets, buildings and magnificent facade details. Vilma Slomp’s images carry an intrinsic ambiguity as they simultaneously document the historic spaces in the city and open possibilities for different narratives. There is a certain interpenetration of internal areas of buildings with strong art deco influence and the eclecticism of exteriors, centred on the symmetry of drawings, the geometric shapes and the monumental aspect of the building.

As a matter of fact, it is possible to interpret the photos as sequence-isolated photograms that materialize in the unconsciousness of the observer. In his/her turn, the observer can create a playful exercise of assembling the images and strolling through Curitiba’s central area, which has undergone extreme transformations in the last decades. The likely narrative created from these static spatial representations taken at different times stir strange feelings for those familiar with the city. The photographs work as communication channels as they express and empower the love for the city even though they were taken at different times.

“Nothing to say, just to show” [3] noted Walter Benjamin in his monumental work Passagens. This is exactly what strengthens Vilma Slomp’s essay. Attentive to the transformations in the city, she documented her city from time to time. The perspective of Curitiba each citizen holds in their memory might be present in this essay. It is the viewer who makes this city, mysteriously and passionately photographed with political awareness of the irreversible progress, pulse again.

It seems inevitable to see the set of photographs as an irrefutable documental reference. However, it is better to understand it as a fictional reading of unstable times and space, meticulously constructed from a sensitive and dedicated look throughout three decades.

The mansion

Photography is not a direct experience; it is cultural, as it is part of a broader context that demands intimacy with the object. Even so, the photograph of a mansion in Marechal Deodoro Street caught my attention. Taken in 1982, it shows an anonymous citizen wandering about the empty sidewalk. In the background, a beautiful mansion with sinuous and symmetric stairs, which suggest embracing the passer-by. The framing prioritises the symmetry of the mansion imposing an aura of silence and respect. The boisterous factor is caused by the uncommon presence of commercial signs – Muricy Photos, Brazil Tailor shop, Restaurant and MF Printing Services. Two other lighting signs jump from the sides facing one another and duelling for more visibility. The vertical image is also filled with a windowless facade and by closed windows in the surrounding buildings. The absence of urban movement, the closed doors and windows indicate it may be Sunday.

In a certain way, this photograph synthetises Vilma Slomp’s essay on Curitiba. In its syntax, the presence of symmetry, of contrasts between old and new, of the history of the city, of the new occupation of old buildings and the metropolitan verticality are noticeable. Vilma snips the city with attentive eyes: what interests her are not only the general and lightly panoramic landscapes but also the details of the sinuous and elegant sidewalk patterns, religious temples, shop windows, hotels, old lighting signs, cafés and pastry shops and street shops, which are slowly disappearing. Everything was meticulously registered to compose a broad and affective panel of the city.

The result is provocative photography. In some images, the contradictory and borderline position between reality and fiction is noticeable. In others, we are moved, haunted and touched. Susan Sontag reminds us that the image taken by the photographic equipment is nearly always a “revelation”. The photographic view, regardless of its objects, signals the presence of mystery. For her, “photography might be, among all, the most mysterious object as it composes and adds substance to the world we identify as modern”.[4]

Influences

Those who still believe photography is an objective possibility of reality, just need to look attentively at Vilma Slomp’s urban photographs: in each photograph, the creator’s subjectivity, as well as her visual repertoire, are evident. It is inevitable to seek an approximation to the great masters of urban photography. When going through Vilma Slomp’s photographs, we not only come across Eugene Atget’s windows, but also Robert Doisneau’s singularity, Edward Steichen’s classic illusion, Berenice Abbott’s modernity of a vertical metropolis and Horacio Coppola’s nostalgia of Buenos Aires and Bernardo Plossu’s of Porto.

As a matter of fact, this project was devised with the incentive Vilma Slomp was given in 1984, when she was invited, along with Luiz Carlos Felizardo and Cristiano Mascaro, to participate in the exhibition Visões Urbanas. The collective project of Funarte’s Photography Gallery was exhibited in Curitiba, Porto Alegre, São Paulo and Florianópolis. Initiated in 1975, the essay Curitiba Central was produced throughout 30 years, aiming at paying a tribute to the city and evidencing the profound changes the urban space went through in that period.

When the famous curator John Szarkowski of the Modern Art Museum of New York called Lee Friedlander’s photographs as “false appearances” and presented an essay by Gary Winogrand as “real world fictions”, he was nearing direct and documental photography to the fictional world. Szarkowski defended the balance between fiction and form representation but always admitted his preference for the fictional power of documental photography.

Vilma Slomp’s photography, taken directly, without artifice, nearly always presents itself as fictional questioning. This photographic vision, tuned in to contemporary trends, creates a certain fascination for the object – in this case the urban space, the city – and searches for evidence of essences of reality. Photography becomes, itself, a possible discourse about the aesthetic potential of photography.

The essay depicts some panoramas of the central area of Curitiba but it is noticeable that nowadays the panoramic perspective no longer represents what the city actually is. In old times, it highlighted reliefs, the sinuosity of rivers, church towers. Nowadays, it shows a snipped drawing of volume buildings, which do not cope with showing the most significant details of the city. “Only in its appearance is the city homogeneous”[5], remarked Walter Benjamin. We know, however, as the essay Curitiba Central shows, that this is impossible from an “imagétique” perspective, though likely as raw material for knowledge and culture.

Vilma Slomp reinforces this idea when documenting with intelligence and sagacity the different “intimate spaces”[6] that hide in the urban territory. This shows us the paths taken by the artist, who consciously opts for an accurate description of the photographer, who stimulates and intrigues the spectator through the presence of expressive resources in the photographic document and also opens up stimulating possibilities to the viewer’s imaginary world.

[1] See Charles Baudelaire, “The Salon of 1859”, in: A modernidade de Baudelaire, Teixeira Coelho (org.), Editora Brasiliense, 1988.

[2] Décio Pignatari, “Times of art and technology”, in: O ensino das artes nas Universidades, 1993, p.27.

[3] Walter Benjamin, Passagens. Editora UFMG e Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São Paulo, 2006.

[4] Susan Sontag, “In Plato’s cave”, in: Ensaios sobre a fotografia. Editora Arbor, 1981, p. 5.

[5] Idem, p.127.

[6] Idem Walter Benjamin.

Rubens Fernandes Junior / 2013

about the book